On a sticky autumn night in North Carolina, two sensations are vying for my attention: the head-to-toe sweat that comes with wearing body armor in this humidity, and the dozens of stings associated with lying on an anthill.

A familiar phrase came from a voice somewhere behind me: "Get in your bubble."

I nodded quietly in understanding.

Targets came up. Bang. Targets went down. The owner of the voice behind me shook his head as he registered that I was the only shooter who downed every target during that phase of a national marksmanship competition.

Editor's note: May is Motorcycle Safety Awareness Month and the best way we can improve our safety is to focus on the things we can control, such as our own riding skills. Alex Hatfield is an instructor at the Yamaha Champions Riding School and a former Army sniper section leader.

Bubbles, OODA, and riding motorcycles

When we ride motorcycles, we are asked to constantly sort through distractions and extraneous information, identify and analyze pertinent information, make decisions based upon our assessments, and translate that into a repeatable, professional action. We do all this at varying degrees of difficulty, largely based on the context of the situation — traffic, weather, road conditions, and so forth. In the military, it's called the OODA loop.

Aside from context, the other major factor that affects our degree of processing difficulty is speed. The faster we go, the less time we have to identify things. This compounds: We have less time to see and identify information, our brain has less time to process even this reduced volume, and so the bits of information that make it through to the decision-making point are generally only the most vital pieces that we identified. Note: Not the most important pieces available — the most important pieces we saw and identified.

Our brains register that we have holes in our understanding and alert us, often through a sense of unease. Effectively, this reduced processing capacity creates a psychological stress reaction. The speed at which we reach that reaction will change with education and experience, but we still need a way to manage it. If we don't, this stress will quickly turn into fear — which can paralyze the entire decision-making process. If we reach that point, we need to consciously force ourselves back into the OODA loop as quickly as possible.

Stress and mitigation

Stress comes in a variety of flavors but is often associated with things happening outside of our control that we're largely unprepared for. In other words, our context often causes stress: Whether we're behind a rifle or behind the handlebar, so much is out of our control.

We have no say in the weather, potholes, or radius of a corner. We can't drive the oncoming car for the driver on his cell phone or move traffic out of our way. We certainly can't ignore the context either; anything we do is going to be shaped by it.

The only real option is to account for and mitigate stress to the best of our ability, then focus on what we can actually control: where we allocate our focus, and how we match our inputs to our needs. This two-pronged approach is how every class at the Yamaha Champions Riding School is taught — and for good reason. By separating what we can control from what we can't, students are given the tools and approaches to mitigate any context they find themselves in. Unfamiliar roads, sudden changes in traffic, qualifying laps on a new track — it can all be overcome with this approach.

The mitigation itself often happens before the ride through things like performing basic maintenance, analyzing a track map, selecting the right protective gear for that day and ride, checking tire pressure, and simply having a plan before getting on the bike. However, this planning step isn't a panacea. It's just one piece of the puzzle.

"Get in your bubble"

We've mitigated the context to the best of our abilities, so let's focus on reducing our stress on the bike. We do this in two ways: physical skillset and mental approach.

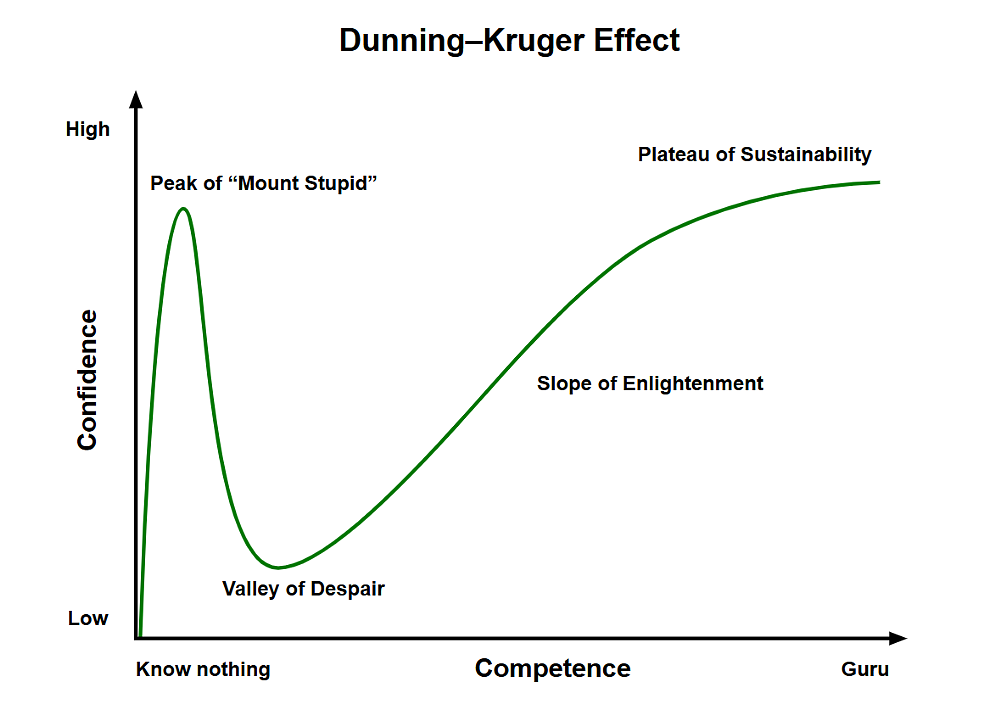

The physical skillset side is developed through focused practice that is grounded in best practices. Leveling up our skills reduces stress through increased confidence. If we're confident in our ability to stop quickly from any speed, to navigate any corner, and to react smoothly and accurately to any stimuli, our stress threshold will be higher. The danger here is a sense of false confidence created by absorbing information without understanding — the kind we usually see in riders atop their Dunning-Kruger "Peak of Mt. Stupid." Yes, I've been there with both a rifle and a motorcycle!

The mental approach is where we truly get into our bubble, so it's time for a mental exercise to truly understand this concept of the bubble. Imagine you're on your motorcycle, on your favorite road or track, but time is frozen around you. Imagine having a physical bubble around you, while you and the rest of the world are suspended. You can see and hear everything around you, but you decide what you focus on — what you let into your bubble. Look around and get a feel for your context. Let's decide what we want to let into our bubble.

We want to know where the road or track goes. We want to keep a watchful eye on traffic. We'll pay attention to the sounds directly around us, giving us information on our competitors or nearby cars. Find that hidden driveway. Notice the puddle on the pavement. Look for that corner exit. All these ordinarily important contextual things are important precisely because they may impact what we are doing; they're the bits of context that may change our OODA loop.

We don't have to let the wafting smell of McDonald's fries distract us. Maybe we're already sweaty in our race leathers, so why worry about the sensation of more? The parked Bugatti in front of Starbucks is cool but doesn't have any bearing on our actions. Distractions like those get to stay outside the bubble.

Now let's hyper focus on a few more things. We want the sensation of a light grip on the handlebar, feeling a finger or two resting lightly on the brake lever. We want to hear our engine. We want to know that our outside knee is pressed into the fuel tank mid-corner, and that our breathing is relaxed and rhythmic. Inside this bubble, we can process all these things. Analyze them. Make decisions. Roll through that OODA loop with a little more clarity and focus. Higher speeds require quicker runs through the Loop.

Now that we're in our bubble and processing truly important things, we devote some focus to the things we can control: our inputs. Let's un-pause time in our mental exercise but keep things in slow motion as we go to the brakes.

Focus on the feel of your fingers against the brake lever, weight increasing on your palms as you feel the motorcycle's weight transfer to the front tire. Squeeze the brake lever harder, building pressure as you feel the rear end rise underneath you. As you come to a stop, smoothly release the last five percent of brake pressure, feeling an almost imperceptible extension of the front forks as the bike settles.

You can go ahead and relax now. I know it probably felt silly to do that, but it's a great way to wrap your head around this concept of the bubble. More importantly, perhaps, it likely introduced you to the mental side of the sport — a place where few of us spend enough time. As Nick Ienatsch likes to tell us, "This sport is 100% mental and 100% physical." We can improve our physical skillset through focused practice, but the real dividends pay off by improving our focus through practice.

Get in your bubble. It's where the champions live.

Membership

Membership